Despite marketing promises, most “coding” toys teach passive button-pushing, not active problem-solving.

- A toy’s true value is its ability to foster hypothesis, testing, and debugging—skills often better developed by simple, open-ended toys like blocks.

- Features like expandability and tactile interaction are far more important than screens or sound effects for developing genuine logic skills.

Recommendation: Before investing, evaluate if a toy demands that the child thinks ahead and learns from failure, or if it’s just an electronic prompt-and-reward machine.

The shelves are overflowing with brightly colored boxes promising to turn your preschooler into a coding prodigy. Robots, tablets, and circuit kits all claim to be the key to unlocking a future in STEM. For skeptical parents, the question is blunt: is this expensive new robot really more effective than a simple set of wooden blocks? The marketing hype around “computational thinking” and “early tech skills” can be deafening, making it nearly impossible to distinguish a genuine learning tool from a high-tech, one-trick pony.

The common advice is to look for something “age-appropriate” or “engaging,” but these platitudes offer little help when you’re trying to decide between a $100 screen-free robot and a $20 app. Many parents default to assuming that more features, lights, and sounds must equal more learning. This can lead to investing in toys that are quickly mastered and abandoned, offering more passive entertainment than cognitive development.

But what if the true measure of a STEM toy isn’t in its electronics, but in the quality of the thinking it demands? The key isn’t the toy’s ability to “teach coding,” but its power to foster active problem-solving. This article cuts through the noise by providing a critical, feature-focused framework. We will analyze what separates toys that genuinely build logic skills from those that merely create cognitive passivity. We’ll examine how to identify toys that grow with your child, the real difference between screen-based and tactile learning, and ultimately, whether these gadgets are worth the investment.

text

This guide offers a structured analysis to help you become a more discerning consumer of educational toys. Explore the sections below to understand the key features that truly matter for your child’s development.

Summary: A Parent’s Critical Guide to Coding Toys

- Why “Push Button” Toys Are Not True STEM Learning Tools?

- Which Coding Toys Grow With the Child From Age 3 to 6?

- Screen-Based or Tactile Coding: Which Is Better for Logic Skills?

- Pink vs. Blue STEM: Are “Girl” Science Kits Watered Down?

- When Is a Child Ready for Circuit Kits Without Frustration?

- How to Use Color-Coded Zones to Guarantee Every Child Gets 5 Eggs?

- Battery Toys vs. Static Toys: Which Generates More Synaptic Connections?

- Screen-Free Coding Robots: Are They Worth the Investment?

Why “Push Button” Toys Are Not True STEM Learning Tools?

The most common pitfall in the educational toy market is the “push-button” phenomenon. These are toys where an action (pushing a button, turning a dial) produces a predictable, singular result (a light flashes, a song plays). While momentarily engaging, this design fosters cognitive passivity. The child isn’t planning, hypothesizing, or solving a problem; they are simply learning a one-to-one correspondence. This is the electronic equivalent of a jack-in-the-box—surprising at first, but offering no depth for real learning.

True STEM learning, especially in the context of coding, is rooted in active problem-solving. It requires a child to form a mental plan, execute it, observe the outcome, and—most importantly—debug the plan when it fails. A toy that only offers success on the first try or has only one “right” way to play robs the child of this crucial learning cycle. The goal is to encourage thinking, not just reacting. Research confirms that toys promoting active, multi-sensory engagement produce better outcomes; in fact, a five-year study revealed that children using such toys had 23% higher problem-solving scores compared to those using more passive toys.

A genuine learning tool functions less like a television and more like a sandbox. It provides the components and the rules but leaves the creation, experimentation, and discovery to the child. The focus shifts from “What does this toy do?” to “What can I do with this toy?” This open-ended quality is what separates a short-lived gadget from a long-term developmental tool.

Action Plan: Audit a Toy for Active Learning Potential

- Hypothesis Formation: Does the toy require the child to think and plan *before* acting, or is it based on random trial and error?

- Multiple Solutions: Can the child test different valid approaches to solve the same challenge, or is there only one correct path?

- Failure as a Feature: Does a “wrong” attempt lead to a clear, understandable outcome that helps the child debug their thinking, or does it just end the game in frustration?

- Adaptability: Does the toy’s complexity grow with the child’s skill level, or is it a one-note experience that will be quickly mastered?

- Child-Led Exploration: Does the child direct the play, or are they merely following a pre-programmed sequence of prompts from the toy?

.

Which Coding Toys Grow With the Child From Age 3 to 6?

A significant concern for any parent investing in a pricey educational toy is longevity. A toy that is captivating at age three but collecting dust by age four is a poor investment. The best coding toys are not single products but expandable systems designed to evolve with a child’s cognitive abilities. These systems introduce foundational concepts simply and then layer on complexity as the child demonstrates mastery.

At ages 3-4, the focus should be on concrete, tangible concepts like basic sequencing and directional thinking. Toys that use physical blocks or cards to represent commands (“forward,” “turn left”) are ideal. As a child moves to ages 4-5, they become ready for more abstract ideas like loops (repeating a sequence) and simple conditionals (“if an obstacle is detected, then turn right”). By ages 5-6, a child can begin to grasp more complex problem-solving, debugging multi-step programs, and even integrating simple sensors.

The key feature to look for is expandability. Does the manufacturer sell additional kits, sensors, or programming blocks that increase the toy’s capabilities? A system that can grow from 10-step sequences to 150-step programs with multiple inputs ensures that the initial investment continues to provide value over several years. This approach scaffolds learning, preventing the child from becoming overwhelmed initially or bored later on.

Case Study: KIBO Robot’s Progressive Learning System

A prime example of a toy designed for growth is KIBO by KinderLab Robotics. It enables young children (ages 4-7) to build and program a robot without any screens. The learning begins with a simple, barcode-based programming system where kids scan wooden blocks to create a sequence of commands. As their skills develop, they can integrate expansion sets that introduce sensors, loops, and conditional statements, allowing for sustained engagement across different developmental stages and proving the value of a modular design.

This table illustrates how different toy systems align with developmental stages, offering a clear roadmap for what to look for at each age.

| Age Range | Toy System | Skills Developed | Expandability |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-4 years | Code & Go Robot Mouse | Basic sequencing, directional thinking | Additional maze pieces, coding cards |

| 4-5 years | Botley 2.0 | Loops, basic conditionals | 150-step sequences, object detection |

| 5-6 years | LEGO Education SPIKE | Complex problem-solving, debugging | Multiple robot builds, app integration |

Screen-Based or Tactile Coding: Which Is Better for Logic Skills?

The debate between screen-based and tactile toys is a major point of consideration for parents. Many coding apps offer a vast range of challenges and can adapt difficulty on the fly. However, for preschoolers, the evidence leans heavily toward the cognitive benefits of tactile, hands-on learning. The act of physically manipulating a block, connecting a piece, or placing a command tile in a sequence engages multiple senses and reinforces the cause-and-effect nature of programming in a concrete way.

This physical interaction, often called haptic feedback, is not just for fun; it’s a powerful learning aid. When a child builds a program with physical blocks, the code is not an abstract concept on a screen—it’s a tangible structure they can see and touch. This helps solidify the mental model of a program as a sequence of discrete, ordered steps. When the program fails, debugging becomes a physical act of finding the “bug” (the incorrect block) and replacing it, making the process of problem-solving more intuitive.

Furthermore, tactile toys inherently encourage collaboration and communication in a way that single-player apps often don’t. Children working together on a physical robot must negotiate, explain their ideas, and jointly solve problems. This social dimension is a critical component of real-world STEM work. Indeed, a global research synthesis found that hands-on, collaborative tasks led to a 41% improvement in collaborative problem-solving among children. While screens have their place, especially for older kids, the foundational logic skills are often best built on the floor, not on a tablet.

Pink vs. Blue STEM: Are “Girl” Science Kits Watered Down?

As you navigate the world of STEM toys, you’ll inevitably encounter the “pink aisle” phenomenon: science kits marketed specifically to girls. These often feature themes of jewelry making, perfume blending, or spa science. A skeptical parent is right to ask: are these kits cognitively equivalent to their “blue aisle” counterparts (rockets, robots, and slime), or are they a “watered-down” version of science?

The answer is nuanced. The cognitive complexity of a kit has little to do with its color scheme or theme. A well-designed kit, regardless of its marketing, will still teach core scientific principles like chemical reactions, states of matter, or engineering fundamentals. The danger isn’t the theme itself but the potential for simplification. A “watered-down” kit is one that prioritizes aesthetics over process—for example, a “crystal-growing” kit that is essentially just “add packet A to water” without explaining the science of saturation and crystallization.

However, some companies have successfully used narrative and character-driven themes to make complex engineering concepts more accessible and engaging for all children, not just girls. These toys prove that you don’t have to sacrifice cognitive challenge to broaden appeal. The critical factor is whether the toy still demands active problem-solving. Does it encourage experimentation? Does it explain the “why” behind the results? Or does it just provide a paint-by-numbers-style craft project with a thin veneer of science?

Case Study: GoldieBlox’s Narrative-Driven Engineering

GoldieBlox emerged as a direct response to the lack of engineering toys marketed to girls. The company’s products combine storytelling featuring a female inventor character, Goldie, with engineering challenges like building a belt drive or a zipline. By integrating narrative, GoldieBlox proved that construction toys could maintain high cognitive complexity while appealing to children who are engaged by character and story. This approach demonstrated that themes traditionally coded as “girly” do not inherently mean a less rigorous learning experience if the core mechanics of building and problem-solving are preserved.

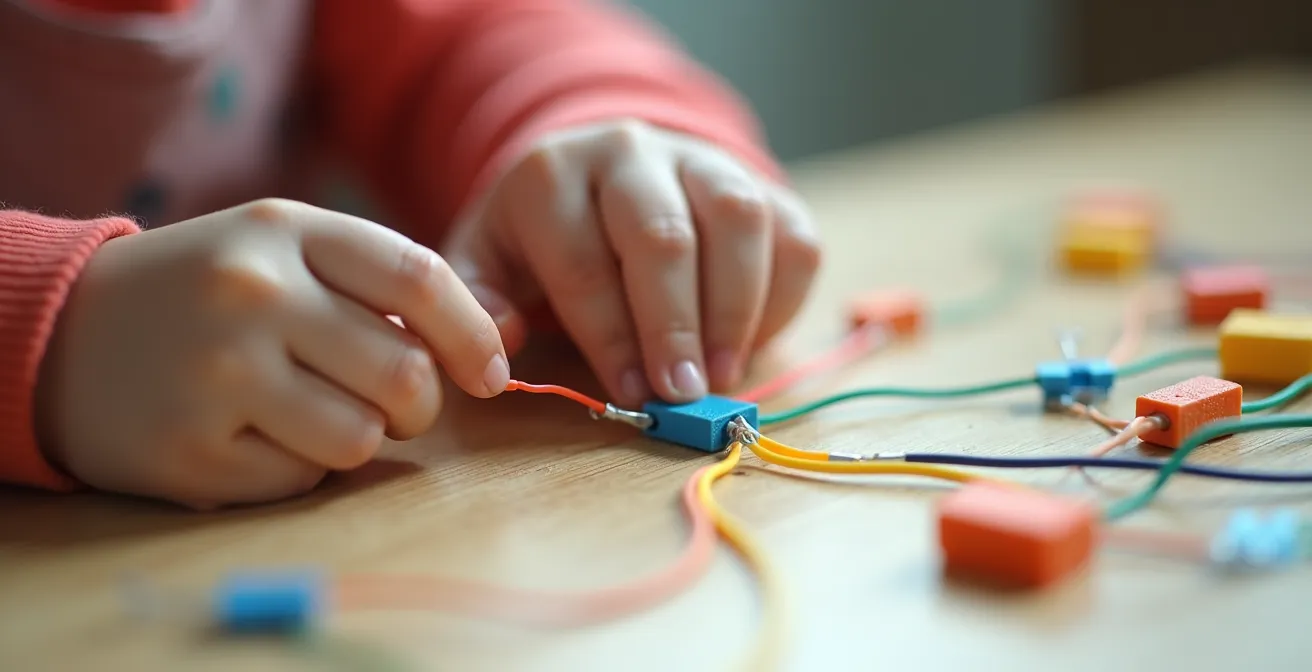

When Is a Child Ready for Circuit Kits Without Frustration?

Circuit kits represent a significant step up in complexity from basic sequencing robots. They introduce fundamental concepts of electronics: power sources, conductors, inputs, and outputs. While powerful learning tools, introducing them too early can lead to immense frustration, effectively discouraging a child’s interest in electronics. A child’s readiness for circuits is less about a specific age and more about a set of observable developmental milestones.

The primary prerequisite is a solid grasp of cause and effect. The child should understand that their actions have predictable consequences. Fine motor skills are also crucial; they need the dexterity to handle and connect small components without assistance. Perhaps most importantly, the child must have developed a degree of patience for trial-and-error. Circuits rarely work on the first try. A child who becomes easily frustrated when something doesn’t work will not benefit from the debugging process, which is where the most valuable learning occurs.

To ease into this world, it’s wise to start with kits that minimize potential frustration. Magnetic circuit kits are an excellent entry point. The magnetic connectors are easy for small hands to snap together and eliminate the complexity of fiddly wires and breadboards. They provide a clear, visual representation of a complete circuit. The satisfying “click” of a successful connection provides positive reinforcement, while a failed circuit is easy to disassemble and reconfigure, lowering the cognitive load of debugging.

Checklist: Developmental Readiness for Circuit Kits

- Visual Instruction: Can the child follow multi-step visual diagrams or instructions independently?

- Cause and Effect: Do they demonstrate a clear understanding that an action (flipping a switch) causes a specific reaction (a light turns on) in their everyday play?

- Fine Motor Skills: Can they confidently manipulate and connect small, intricate objects?

- Patience with Process: Do they show resilience and curiosity when a building project or puzzle doesn’t work, or do they give up quickly?

- Verbalizing Problems: Can they attempt to explain what they think went wrong when something fails (e.g., “I think this piece is backward”)?

How to Use Color-Coded Zones to Guarantee Every Child Gets 5 Eggs?

This oddly specific question about an egg hunt is a perfect, real-world analogy for teaching algorithmic thinking without any technology at all. At its core, an algorithm is simply a set of rules or instructions designed to solve a problem. The “problem” in an egg hunt is ensuring fair distribution. Just telling kids to “find 5 eggs” often results in some children finding ten and others finding one. A simple algorithm can solve this.

Imagine you create three color-coded zones in your yard: red, blue, and green. You then establish a rule: “Every child must find two red eggs, two blue eggs, and one green egg.” You have just introduced variables (the colors) and conditions (the required count for each). The children are now executing a program. This transforms a frantic dash into a strategic, problem-solving activity. They are no longer just searching; they are executing a plan and tracking their progress against a set of constraints.

The most valuable learning happens during the “debugging” phase. What happens when a child has two red eggs and can’t find any more? They have to adjust their strategy, perhaps by helping another child who has found too many. This process of using rules, managing resources, and adapting a plan is the very essence of computational thinking. As researchers have found, using physical activities like this to teach algorithmic concepts can significantly increase a child’s understanding of core programming ideas like conditionals and even parallel processing.

This principle extends far beyond holiday games. Daily routines are filled with opportunities to practice algorithmic thinking:

- Setting the table: Create a “program” for the placement of each item (fork left, knife right, spoon above).

- Sorting laundry: Use “if-then” logic for colors and fabric types (e.g., “IF it’s a sock AND it’s white, THEN it goes in this pile”).

- Making a sandwich: Sequence the steps and handle “errors” like running out of an ingredient.

Battery Toys vs. Static Toys: Which Generates More Synaptic Connections?

This question gets to the heart of the skeptical parent’s dilemma: are fancy, battery-operated toys inherently better for brain development than classic, static toys like wooden blocks or clay? The neurological answer is often a resounding “no.” The number of synaptic connections a toy helps generate is not related to its price or power source, but to the degree of open-ended, creative problem-solving it demands from the child.

A battery-powered toy, by its nature, has a pre-defined set of functions. It’s programmed to do specific things. While these can be complex, the range of possibilities is ultimately finite and determined by the manufacturer. A set of simple wooden blocks, however, has a nearly infinite number of combinations. It can become a castle, a car, a bridge, or a spaceship. This lack of pre-determined outcome forces the child’s brain to do the heavy lifting: planning, spatial reasoning, testing physical stability, and exercising creativity.

As experts in the field note, this open-ended quality is a powerful engine for cognitive growth. It’s the difference between following a recipe and inventing a new dish.

A static toy like a set of wooden blocks offers infinite combinations, forcing the brain to create new pathways for spatial reasoning, planning, and creative problem-solving.

– Dr. Wei Xiao & Alexandre Gonçalves, Intelligent toys, complex questions: A literature review of AI in children’s toys

This isn’t just theory; research consistently shows the power of unstructured play. A synthesis of global research demonstrated that children engaged in open-ended play with basic materials achieved 28% faster mastery of STEM concepts than those using more structured, single-purpose toys. A battery toy may capture attention, but a static toy captures the imagination—and it’s in the realm of imagination that the most profound learning and synaptic growth occur.

Key Takeaways

- A toy’s educational value is determined by its ability to provoke active problem-solving, not by its lights, sounds, or marketing claims.

- The best coding toys are expandable systems that grow with a child’s abilities, introducing complexity in stages.

- For preschoolers, tactile, hands-on toys are generally superior to screen-based apps for building foundational logic and debugging skills.

Screen-Free Coding Robots: Are They Worth the Investment?

After deconstructing the hype, we arrive at the final, practical question: are screen-free coding robots actually worth the significant financial investment? The answer depends entirely on a critical analysis of cost versus the skills being taught. A high price tag does not guarantee a high educational return on investment. Some of the most expensive robots offer little more than basic sequencing, a skill that can be taught with far cheaper alternatives or even, as we’ve seen, with an egg hunt.

A feature-focused analysis requires you to break down what you’re paying for. A robot’s value can be measured by its “cost per skill.” A $50 robot that only teaches sequencing has a cost of $50 per skill. A $90 robot that teaches sequencing, loops, and conditionals has a cost of $30 per skill. This framework helps you look past the slick design and assess the actual educational density of the product. The goal is to find the toy that offers the richest, most expandable feature set for its price point.

The market for these toys is growing rapidly, with analysis suggesting the global STEM toys market is expected to grow at 8.8% CAGR from 2025 to 2034. This growth means more options, but also more noise. As a discerning consumer, your best tool is a simple table comparing features against cost.

This cost-per-skill analysis of popular screen-free robots reveals that price is not always an indicator of educational depth. Some lower-cost options provide a more efficient entry point into multiple coding concepts.

| Robot | Price Range | Skills Taught | Cost Per Skill |

|---|---|---|---|

| Code & Go Mouse | $40-60 | Sequencing, Problem-solving | $20-30 |

| Botley 2.0 | $80-100 | Sequencing, Loops, Conditionals, Object Detection | $20-25 |

| Cubetto | $225-250 | Functions, Sequencing, Spatial Reasoning, Debugging | $56-63 |

Ultimately, a screen-free robot is “worth it” only if it meets the criteria we’ve established: it promotes active problem-solving, it’s expandable, and its feature set justifies its cost when compared to alternatives. Often, a combination of a simpler robot and a good set of wooden blocks provides a far richer and more cost-effective learning ecosystem than a single, expensive machine.

Now that you are equipped with a critical framework, the next step is to apply it. Evaluate the toys already in your home and any future purchases not by their marketing, but by the quality of thinking they demand from your child.